|

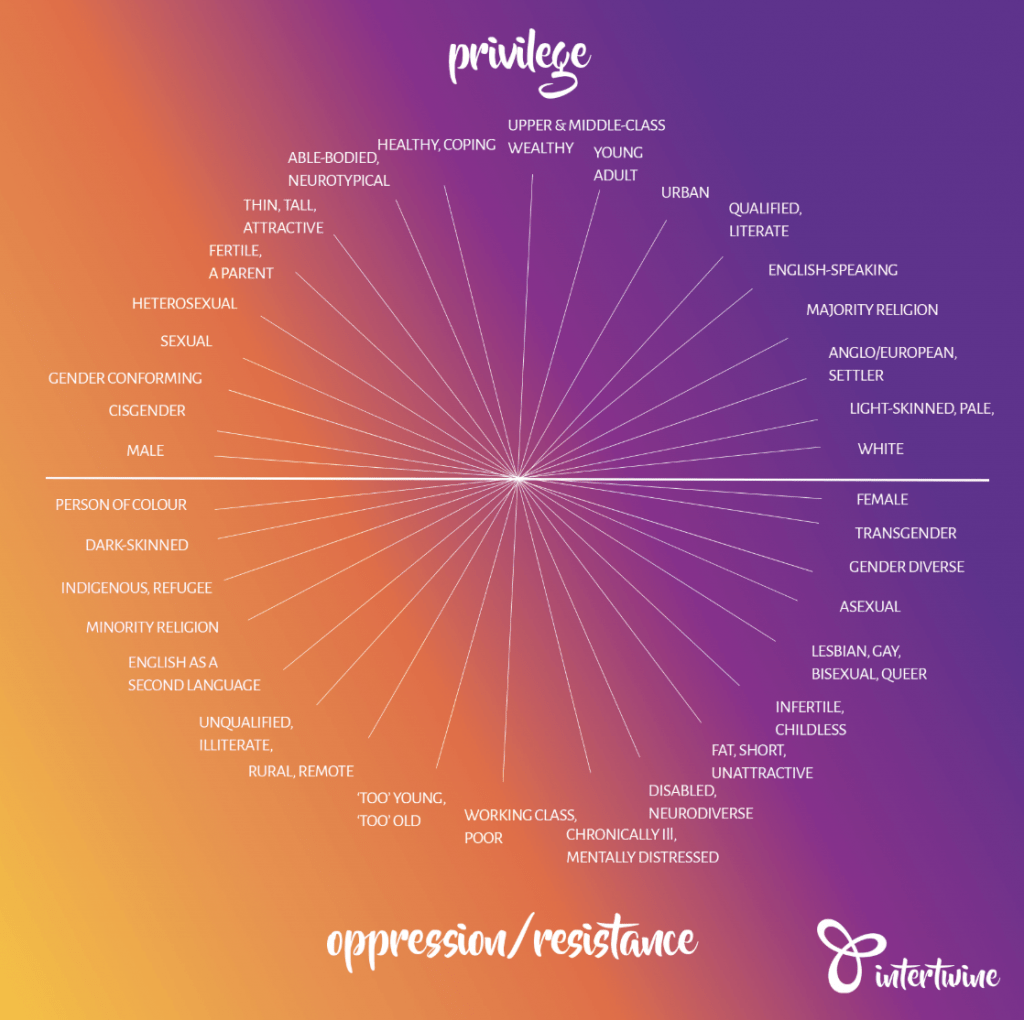

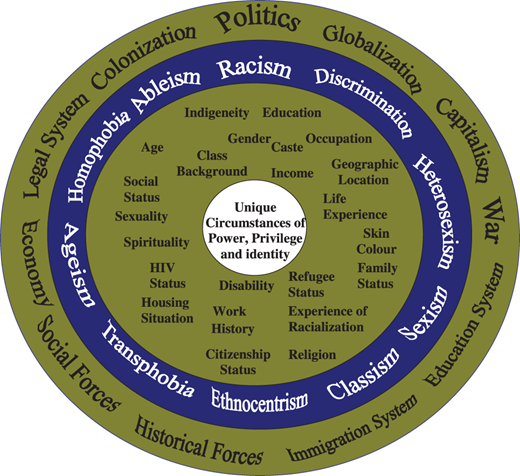

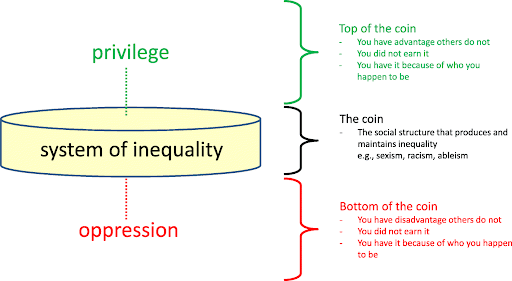

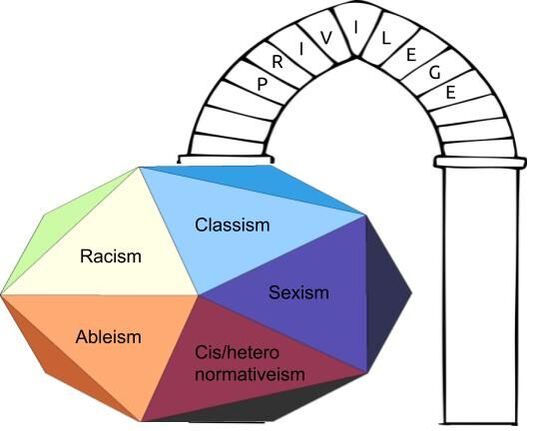

As a movement that was founded in the United Kingdom, activists in Toronto have questioned the appropriateness of Extinction Rebellion’s (XR) demands, structure and strategy to a Canadian context. Working groups focused on decolonization and solidarity have emerged, as has the crafting of a fourth demand that calls for justice for all (Julius, 2019). Despite this, XR Toronto still is composed largely of white, middle-upper class folks, consistent with criticism of the organization in general (Lewis, 2019). There has been much deliberation among those of us who consistently show up around how to welcome and raise the voices of those who tend to be systematically oppressed. It has been noted in the academic literature that activism and advocacy almost always comes from a place of power and privilege (Pollock, 2018). When a person or a community can meet their basic needs, there is more capacity to devote time, energy and other resources to activism. In fact, it has been argued that systems of power and privilege have been deliberately constructed by the elite to control and oppress others (Allen, 2001; Thandeka, 2018). (On the other hand, there are abundant examples in which groups organize(d) against oppression in order to demand their basic rights. The efforts to stop deforestation in the Amazon is an example in which Indigenous communities disproportionately affected by ecological degradation have for many years been pushing back against transnational corporations (Toohey, 2012). Saul Alinsky left a legacy of social changes driven by local movements (Bretherton, 2012)). Privilege is a broad term, one that is relative and often fraught. I have had my attention drawn to the importance of inserting the qualifier unearned or “over advantaged” (DiAngelo, 2016) to distinguish between ways that individuals benefit due to systemic injustices as opposed to privilege that one has earned through their efforts. On the flip side of unearned privilege is oppression - the experience of being denied privilege or even equity based on some aspect of experience or identity beyond one’s control (Figure 1). I have for some time been mindful of my positionality with respect to privilege, advantage and power. I have participated in anti-oppression training on multiple occasions, and have encountered numerous opportunities to reflect on my position and how I benefit from systemic inequities. However, whereas “anti-oppression” is often about avoiding disadvantaging others (Harlow & Hearn, 1996) - perhaps it could be thought of as harm reduction - I was introduced during a course to Stephanie Nixon’s coin model (2019), which speaks more to the importance of actively seeking opportunities to dismantle the systems and structures (ie. the coin on the top or bottom of which an individual sits) that allow unearned privilege/disadvantage to even exist. She points out that systems of power and privilege disadvantage everyone - including those on the top of a particular coin - by silencing and marginalizing valuable voices, reducing the possibilities of diversity and innovation, solidarity and collaboration. Unitarian-Universalist minister Reverend Thandeka also posits that systems of inequity also act to silence individuals who might otherwise be allies as they attempt to cling to the power they have (2018). This is very parallel to the recognition that greater income polarization within a society correlates to poorer health for the entire population (Dunn, 2002; Inequality and Health, n.d.). Making the dynamics more complex is the concept of intersectionality, which refers to the holism of a person’s identity and experience: the concept that no one can be reduced to a single aspect of identity affecting their personal experience of privilege, oppression or power. The totality of one’s experience of oppression is likely more than the sum of its parts, and is relative to the particular context/community/environment in which one operates (Crenshaw, 1991). Systemic oppression may also be mitigated by other elements of privilege (eg. a young black male whose family has been in Canada for 100 years and who’s father and grandfather were university graduates will have more power, privilege and social capital than a young black male who is a recent immigrant from Nigeria). The exercise I’ve engaged with previously that has most poignantly demonstrated the impact of systemic injustice and intersectionality is one in which participants move forward or back along a line or into a circle depending on their experience of various statements of identity. What this exercise fails to do, however, is put the light on the structures that create these experiences. Nixon’s coin model draws one’s attention to the necessity of those sitting on top of a particular coin to deliberately look for ways in which they are complicit in the existence and perpetuation of that coin (2019) (Figure 3). Since the very existence of a coin results in those on its top perceiving their experience as “normal”, it requires training of one’s eye and mind, and an explicit choice to engage in that process of seeing, unlearning and dismantling. Layering the concept of intersectionality onto the coin model brings to mind a distorted multi-faceted polyhedron, a three-dimensional model that comes even closer to approximating the lived experience of a person. Each face is an individual coin, each with a unique influence (represented by its dimensions) on the experience of a particular person in a particular time in a particular place. The number and size of each face affects the overall size of the figure, and the larger each face is, the more difficult it may be for that polyhedron to get through the metaphorical door of privilege (Figure 4). Acknowledging that one’s success - material or otherwise - may not always be completely earned by one’s own efforts flies in the face of the neoliberal culture's deeply held valuation of meritocracy (McLean, 2018). It requires deconstruction of the myth that there are many aspects of “success” that are not earned (in quotations since the same systems perpetuate biases about what is considered success), and are beyond control of the individual. This can be highly uncomfortable, and elicit feelings of guilt, anger and defensiveness in those on the top of any coin and corresponding behaviour that ultimately reinforces the status quo - poignantly described as “fragility” by DiAngelo (2016). In the current Toronto context, I am a beneficiary of socio-political forces that value most of the features of my identity. As a white descendent of settlers, able-bodied, fertile, ostensibly cis- and heterosexual, ostensibly Judeo-Christian, English-speaking, academically educated (etc.) woman, I see much opportunity for growth and learning with respect to my role in perpetuating or dismantling systems of privilege. I am very aware of the importance of mitigating the power that I have in the system that currently exists. I am aware of the importance of continuing to educate myself on the mechanisms of privilege and power, and to train my eyes and ears to see microaggressions and to recognize oppression even when it doesn’t directly affect me. Nixon poses challenging questions that help to frame this work: “In what way did I benefit from a structural inequity today; in what way did my actions contribute to that system?” However, I continue to bump up against some challenges. The idea - and importance - of making mistakes along this learning journey has been held up in anti-oppression training. However, I struggle with how making mistakes as a productive struggle intersects with the way in which my mistakes - even if I recognize and make honest amends for them - cause harm to others in the form of a micro (or macro) aggression, or forces someone on the bottom of a particular coin to engage in the emotional labour of educating me. While I may be willing to engage in dialogue about these issues, the other person may not. At what point are my sincere curiosity and willingness to dissect an exchange signs of fragility vs. a desire to learn and grow in solidarity? Nixon affirms (personal communication, 2020) that my desire to learn and grow must not rely on the expectation that the other must also engage. In a recent exchange with a Person of Colour, my curiosity about a sentiment that white people “never” understand structures of privilege and oppression was viewed as racist. This individual seemed to use DiAngelo’s work to frame my question as evidence of fragility. I spent days turning the exchange around and around in my mind, and talking to trusted mentors, trying to make sense of it. My minister - who is a PhD candidate and actively engaged in anti-oppression work - suggested to me that when taking DiAngelo’s concepts at face value, “there is no way to get off the hook” (S. Newton, personal communication, May 21, 2020). I worry that accusations of fragility in people with power (of any sort, not only the construct of race) undermines the potential for solidarity. Nixon suggests that DiAngelo's argument is more nuanced. Is it possible to do the work of mitigating systemic injustice while simultaneously practicing the vulnerability that is the foundation for building trust and solidarity? When we engage in a productive struggle, take responsibility for the ways in which our actions cause harm (intentionally or otherwise), and strive to hear and understand the pain of others, it builds trust and reinforces the motivation to continue doing the work. It is difficult to be an ally to someone who frames critical curiosity as proof of fragility rather than a desire to grow in solidarity. During the exchange described above, I was told that any discomfort I might be feeling was good, because then I would know how People of Colour feel. I struggle with the idea of discomfort as retribution for the sins of my settler ancestors (Thandeka, 1999), as opposed to a rich opportunity for growth. Systems will be dismantled through collective action by those who are willing to do the work, no matter how they self-identify. As suggested by Syed and Hill, personal relationships allow for the process of moving into a space where ‘a-ha’ moments become possible (2011). I appreciate the importance of choosing to reduce the wielding of my power and to deliberately elevate and amplify the perspective of others. But if any critical response of mine is unwelcome or framed as defensive simply because of my unearned advantage, how can learning and solidarity occur? It makes me wonder about the intersection between issues of racism on a systemic level, and the place of relationship building on an interpersonal level. DiAngelo suggests that white people have not developed racial stamina and do not have the cognitive or emotional resources to engage constructively with respect to race. Is it not possible for a white person to have a thoughtful, measured response without being dismissed as fragile? Is it reasonable to expect someone who has spent a lifetime being vigilant to aggression and oppression and violence to respond with anything less than anger to my curiosity? Nixon points out that People of Colour are justified in their anger, and asks if I am able to hear and hold that anger as a medium for healing, and a path to a more productive relationship (S. Nixon, personal communication, May 22, 2020). She points out that discomfort is a far cry from a lack of safety: at what point does my willingness to be uncomfortable infringe on someone else’s sense of safety? Nixon wisely suggests that I humbly receive these experiences as a gift, and unwrap that gift with those who wish to do that work with me. Thus this reflection. DiAngelo speaks to the premise of universalism. Interestingly, this is a core tenet of the nonviolent communication framework developed by Marshall Rosenberg. Rosenberg posited that all humans have needs, and that needs are universal (Wechsler, 2018). By entering into conversations from a place that seeks to understand one’s own needs, and the needs of the other person, compassion and connection can grow. This requires skills of emotional intelligence, and a mindfulness of thoughts, feelings and sensations that can give us clues as to what needs of our own may not be met. It requires recognition of cues in others that may help us understand their needs. It requires the nurturing of loving compassion in order to hold the suffering of another without placing it above or below our own - although in the case of power and oppression, there is a deep inequity in the degree to which we suffer. By actively honouring the experience of another person, even if I don’t fully understand it, I give space for and can nurture compassion. As Reverend Thandeka advocates, we can “use our collective power … to help each of us heal our crippled ability to relate with the full integrity of our humanity” (2018). Articles written by others since I posted this that circle around my difficulty with this dilemma (one written by a Black woman, one by a white man): It's Time to Retire the Term White Privilege Dear White People: Please Do Not Read Robin DiAngelo’s “White Fragility” References

0 Comments

|

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed