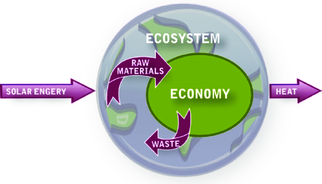

Preamble As a healthcare provider, I quite thoroughly understand concepts of homeostasis, inputs and outputs, and growth vs. maintenance vs. decline within the body. I grasp the details of how ecosystems handle this homeostasis less thoroughly, but appreciate the logic of a steady state. The idea that human activity on this planet must follow the same laws of nature has always felt intuitive, and I have struggled with the assertion that technological “progress” would ever allow the human species to transcend these laws. This is relevant to my choice of profession as well; our collective value systems refuse to see our own bodies as susceptible to the laws of nature; we abuse ourselves like we abuse the planet (often in the same action), and assume that technoscientific, reductionist “medicine” will fix us. That ethos is driven by the same forces that drive ecological breakdown … capitalism, instant gratification, contemporism, anthropocentrism. Based on my naive (admittedly willfully so) understanding of economics, which I assumed was synonymous with growth, I believed the field as a whole to be directly contrary to any possibility of sustainability. The concepts of ecological economics are beautiful in the way they apply natural laws to the management of capital. The economy is a subset of - not independent from - the larger ecosystem, and is thus subject to its laws and limits (Daly, 2008).

The problem of infinite growth

Malthus (1872) posited that the planet had a limited capacity to sustain the nutritional needs of a growing population. Although he was wrong with respect to that particular relationship at that time, the core principle still holds. Food insecurity and famine IS a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide; however, this is not due to population growth alone, but to collective and exponential growth in consumption, extraction and waste overall. With a small enough population, an ecosystem can be exploited and the community can move on, giving the area an opportunity to regenerate. Collectively we can no longer do this because there are too many of us and there is no place to go (back to Malthus), unless we are Elon Musk or Arnold Schwarzenegger escaping to Mars. The widespread consequences of the insistence on growth as the measure of success and progress has placed unsustainable demands on scarce and non-renewable natural resources, most notably fossil fuels. This is not to fulfill the basic needs of a large population, but to fatten the offshore accounts of those at the pinnacle of the systems of capital. Genetically modified organisms, as one example, are touted as being the solution to global hunger, when really they serve more to increase the profits of Monsanto shareholders at the expense of the sovereignty and health of small farmers (Jansen, 2015; Gupta, 2015).

Our current economic systems were designed by those with political/economic/social power to perfectly fulfill the goal of concentrating wealth at the expense of the planet and other people. Wealth accumulation depends on extending one’s borders (imperialism and export of waste), exploiting others’ labour (slavery, outsourcing), and extracting more resources than can be efficiently replaced (planetary destruction). The dominance of these systems (and the values that underpin them) have resulted in growth and gross domestic product (GDP) being used as a measure of wellbeing. The emphasis on GDP and the conspicuous consumption required to drive it reasonably results in the desire and expectation that all inhabitants of “Spaceship Earth” (Boulding, 1966) should enjoy the same pleasures of life as those with the most wealth. The entire social and political system is rigged to convince us that we should want more, are entitled to more, and can access more if we work hard enough. (Boulding pondered in his paper why Eurocentric cultures rose to global dominance in the middle ages as opposed to China; certainly this is a complicated query, and there is abundant scholarship exploring the answer. European cultures which dominated and colonized much of the world were fundamentally Christian, the values of which emphasize dominance and individualism. The pursuit of dominance and wealth depends on high levels of energy input, and necessitates oppression and exploitation. These principles, rooted in the Christian system, are deeply infused into the Eurocentric/western collective value system, underpinning capitalism, white-supremacy, patriarchy, meritocracy, anthropocentrism (Batson et al, 2020).)

Let’s set aside for now the blatant and racist mythology of meritocracy. Although income is one of the strongest predictors of health and well-being (Patel & Kariel, 2021), excess wealth is not correlated with increased happiness. Being able to meet basic needs (not only physical needs such as food and shelter, but also psychological and social needs such as autonomy and control) are critical for happiness and health. Although interventions such as a universal basic income may be helpful to address inequities in the short term (Gibson, Hearty & Craig, 2020) and contribute to driving GDP, they still perpetuate the idea that a free market economy is ideal, that infinite growth is feasible, and that access to basic needs should be commodified. In fact, the classic experiment in Finland concluded that basic income support is not sustainable in a growth-oriented economy (Kangas, 2019). “Environmental” economics is unlikely to be the solution if it still emphasizes growth as the goal. Despite the best efforts of those who cling desperately to neoclassical economic theory, the ecological crisis will not be averted by a reliance on the same system that created the problem. The criteria for a perfect market are far from being met, and without an honest calculation of costs, there is no natural cue for growth to cease (a la Coase). A faith in technoscientific “solutions” to the environmental crisis also disregards the concept that we are in an open system. As Daly points out, human-made replacements for natural resources still require input from nature, and have costs in the form of effluvium. As a wise woman once asked, how many windmills does it take to make a windmill?

A friend of mine is an adherent of technology, and an avowed vegan. He told me that he buys “cheap plastic” shoes to avoid leather. While I respect his integrity, what he fails to grasp is that those “replacements” still require the input of natural resources, which cost more than leather which lasts much longer and can be more effectively repaired than cheap vinyl substitutes. This doesn’t preclude the need for buying less in general and fixing what we have. I am absolutely an advocate for mindful consumption of both sustainable wearables and a plant-based whole food diet - just not chemically-manufactured “substitutes”.

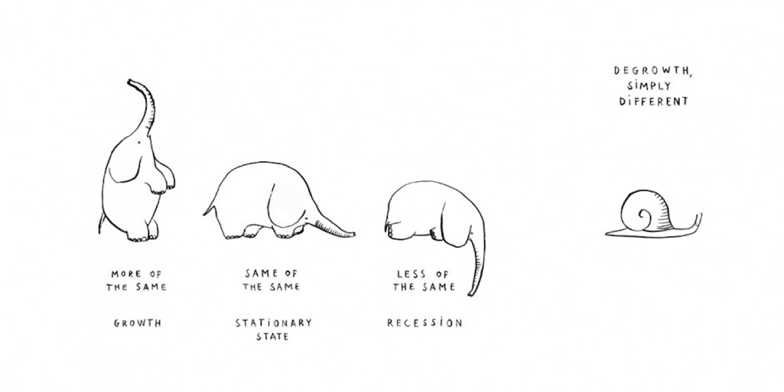

Even if it did function effectively, the free market - being inherently reliant on competition - disregards justice, placing a disproportionate burden of costs on vulnerable individuals, communities, species, and ecosystems. If keeping throughput below the level that the natural environment can accommodate is the only logical approach to mitigating the worst of the planetary crisis, justly determined policy is urgently required to design and empower a system with an emphasis on equity (reference my paper), which is only possible if we shatter the fetishization of growth and GDP. Using GDP as a measure of well-being is only possible because of its distortion and manipulation of costs. If we are honest about what the costs are, what they are worth, and who carries their burden, it would be quickly apparent that the costs of our current patterns of consumption and waste dramatically exceed their benefits. As Daly puts it, collectively, our planetary system is in a UNeconomic state. We are collectively getting poorer, not richer. Deliberate economic degrowth is urgently critical if the planet has any hope of healing (Kallis et al, 2012).

The challenges shifting to degrowth

If we are collectively getting poorer, those with wealth and power are getting proportionately richer in the short term - not only the Bezos’ and Gates’ of the world, but many in higher-income countries. Those who benefit from and are complicit in a growth-oriented economy (ie. those who have the disposable income to enjoy conspicuous leisure, consumption and waste) would rather resist change until the biosphere collapses. Boulding despaired in 1966 that no one was listening, possibly because the fall was a long way off. It is closer and more obvious now, with accelerating frequency and severity and visibility of “natural” disasters, global pandemics, mass migration and conflict. And we are still resisting. We see this right now as Alberta and Saskatchewan rail against the Supreme Court decision to uphold the federal carbon tax. Those provinces argue for a cap and trade system, which still puts the emphasis on the market to work it out . Although this at least counts carbon emissions as costs, it still perpetuates the importance of economic growth, placing greater emphasis on proximal consequences vs. distal (geographic or chronologic) costs, and places the economy ahead of the environment. If those with power are willfully ignorant to the logic of ecological economics, the real tragedy of the commons is that most people are ignorant by design (quothe my friend James). Most of us have been raised to be cogs in the machinery of production and consumption and waste. We must labour to ensure our needs and wants are met. Social services “disincentivize work”. We are kept distracted by “entertainment”, which in reality serves to perpetuate these norms. Policy decisions that have placed too much power in the free market have created such a lack of “trickle down” that many are just trying to hold on. The economic principle of time discounting, arguably synonymous with the psychological tendency to contemporism, makes it difficult to act for the future.

The pacification of philanthropy

We may be emotionally moved by pictures of starving Yemen children, or koala bears displaced by Australian fires. Our guilt may be temporarily assuaged by a charitable response to inequitably borne consequences of planetary breakdown. This is defended by some as an essential redistribution of wealth, but philanthropy will never correct the problem, doesn’t offset the harms of an unsustainable lifestyle, and is part of the same capitalistic, hegemonic mechanisms of the broad economy (Morvaridi, 2012). Those making donations benefit from accolades and/or tax credits (until they get audited if they donate more than 5% of their taxable income because it is viewed as more suspicious than hoarding or blowing it in the pursuit of pleasure).

Even those who appreciate the consequences of a growth-oriented economy and wish to opt out find it nearly impossible to completely disentangle from it, and often face social consequences for trying. Not only is it difficult to resist powerful forces of propaganda (eg. marketing), industrial design (eg. planned obsolescence), social practice (eg. need for convenience), and social norms (eg. fast fashion), in order to meet one’s basic needs in the current system, one still must adhere to its rules of working to bank capital for later in order to survive. Those who don’t are lazy or crazy, and are blamed for their addictions and “disabilities” and lack of “success,” defined by net worth.

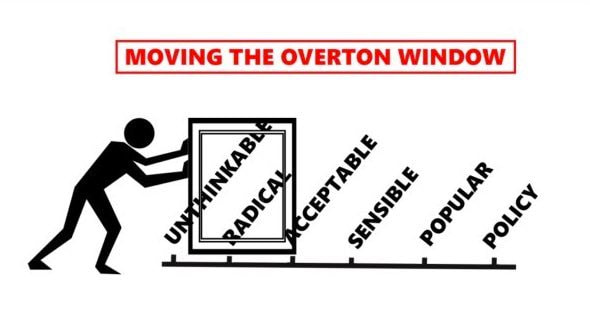

Shifting the narrative There is an urgent imperative to perpetuate the reality that infinite growth is ecologically impossible, even if it was wise or just. We must collectively reduce our demands on the natural world. As Boulding articulated, “the less consumption we can maintain a given state with [sic], the better off we are.” This also conjures Gandhi’s advice to “live simply so that others may simply live.” We must value measures other than GDP: health indicators, education, happiness, local and planetary biodiversity, how much free time we have - as Boulding says, “the nature, extent, quality and complexity of the total capital stock.” Perhaps rather than a competition for high GDP, we celebrate low GDP as a sign of wellness and equity. This needs to be sold not as a sacrifice we must make for the greater good, but as the truth: that a simple life is not an anemic one (Alexander, 2014). A new TV won’t make you sustainably happy. However, the pleasure of eating food grown yourself, deep conversation with friends, making music, reading and trading books, fixing things, moving, spending time in nature … these are the joys of life. Overton’s window (Mackinac, 2020) suggests that elected representatives will support policies that are likely to get them re-elected. This policy window is wide or narrow, and slides along a spectrum of acceptability to a particular community at a specific place and time. In times of stability, the window shifts very little (Schmitt et al, 2020); thus, applying strategic tactics at times like we are in now that aim to shift the window of what is deemed acceptable will ultimately shift policy. The body of literature on the concept of “radical flanking” as a means to shift the window is intriguing. Of course, this necessitates electoral reform so that this view extends beyond a myopic four years, and must also occur globally and simultaneously, due to the resulting disruption of international relationships. It is beyond the scope of this response paper to explore the coordination of all the tactics that will be necessary to transition to an ecological economy.

Boulding points to “American Indians on reservations” as being an example of knowledge and information degradation, but this isn't accidental. The reservation system and associated colonial policies were a very deliberate attempt at (ongoing) cultural genocide in the name of imperialism and wealth concentration. Had the Indigenous nations of Turtle Island and the rest of the planet not been colonized by European conquistadors and deeply wounded by capitalistic mechanisms, it is very possible that the evolution of those knowledge systems would have resulted in a very different global economy and circumstance.

Reconciliation is not about simply making amends for generations of trauma inflicted. It is about humbling ourselves. We are all descendents of Indigenous cultures. There is much we must re-learn from Indigenous worldviews. It is critical to amplify and cultivate traditional knowledge, not only on Turtle Island, but world wide. We must apply principles that center circularity, sustainability, and reciprocity as opposed to linearity and power. The Dish with One Spoon Wampum which covers the Great Lakes area captures the sentiment of this beautifully. It speaks to the land as a dish we all share, eating from the dish with one spoon. We must ensure that everyone has enough, that the dish is kept clean, and that the dish is never empty. Most importantly, there are no knives at the table.

Core Values of a Degrowth Economy

There are some core values that should underpin first a degrowth and then a stable-state economy. It seems necessarily and intuitive than any principle of ecological economics would intrinsically necessitate seeing the human species as part of nature rather than separate from or above it. It would require a valuation of nature not as a resource or an “input”, but something with inherent worth, which implies that all humans, species and ecosystems must be valued as having inherent worth, and deserving of being treated with justice and dignity despite their “contributions” to GDP. Ingebrigtsen and Jakobsen have proposed some core principles of ecological economics (Others have attempted a similar articulation, but for the purposes of this piece, I will start here; interestingly, but not surprisingly, these principles overlap with those of the planetary health movement, and many Indigenous traditions (Prescott et al, 2018)):

Conclusion

Boulding argued in 1966 that we lacked the moral, psychological and political adjustments needed to shift our economic thinking. I would add that this translates to knowledge for some, willingness for others, and courage for the rest. Often it is observed that I am an “environmentalist,” instead of a rational human who sees the consequences of our current system and imagines that it doesn’t have to be this way. I am often told that riding my bike, hanging my wash to dry, eating mindfully, not purchasing minimally and deliberately, fixing and reusing what, etc. are insignificant actions. Perhaps so, in the grand scheme of things, but it certainly creates conversation and discourse, possibly shifting the narrative, especially when partnered with strategic action and advocacy for policy change. As Boulding says, modest optimism is better than no optimism at all. (Need to hear it from someone else? Watch the video below)

References

0 Comments

|

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed