|

Disclaimer: My knowledge of Indigenous-settler relations and history is superficial at best, and I am continuing to evolve in my understanding. I write this from a place of love, curiosity and a desire to engage in reconciliation.

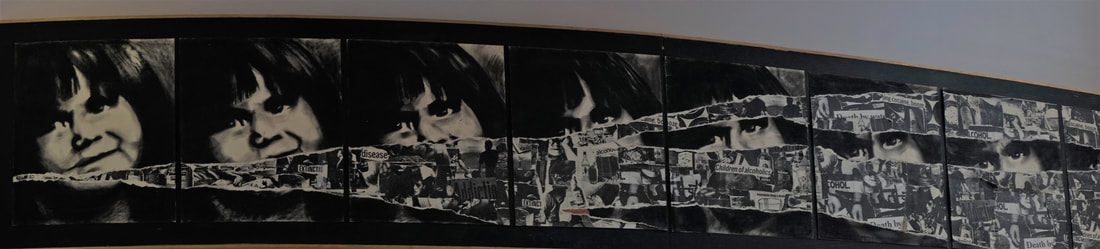

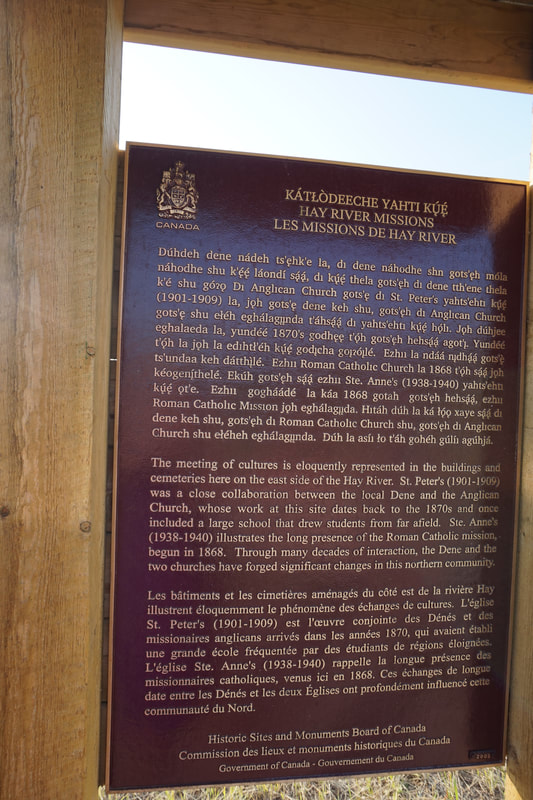

I’ve landed back in Toronto after my summer in the Northwest Territories. I learned a tremendous amount about holistic land management, communal living, and history and culture in the north - and of course I left with more questions than answers. I was also privileged to have the opportunity to be both participant in and observer of the Indigenous-settler dynamics in Hay River. The K’atl’odeeche First Nation (KFN) is the only reserve in NWT (though there are of course many Indigenous communities). It sits on the opposite side of the Hay River from the town, a powerful geographic separation (except in the winter when the winter road links the two communities). It’s a beautiful community with deep connections to the land, rich family bonds, and strong ties to history. I was privileged to be present at gatherings both joyful and mournful, to be welcomed into celebrations and offered the gifts of language and food and dance and art. KFN, like most Indigenous communities in Canada, has been impacted by systematic racism and trauma inflicted by colonialism and European settlement. Conversations with local Dene people, local Canadian folks of European descent, and international volunteers shed some fascinating light on how things came to be. I heard from Indigenous and white folks alike about the struggles in the community. The rate of highschool graduation is low and living conditions are often poor; elders expressed that young people are not interested in traditional language and culture; I heard that there is a tendency to short term vs. long term thinking and planning; there are high rates of chronic health issues including diabetes. I heard concerns about substance use and fears for personal safety, and a lack of trust in the territorial/colonial police and social services. I experienced a number of situations when colonial expectations about scheduling conflicted with an Indigenous worldview of timing. It struck me over the summer how well-kept a secret is Canada’s history of cultural genocide. I had conversations with many of the farm’s international volunteers, all of whom were unaware of the residential school system, the Sixties Scoop, the dishonesty in the negotiation of Treaties, unfair trading practices, illegal capture of land, and the introduction of deadly diseases. To them, the way seemed clear. If kids weren’t finishing highschool, just bring in a motivating teacher to inspire them! When I shared my experiences working at an Indigenous health center in Toronto, they couldn’t grasp why clients needed time to come to trust me - after all, it wasn’t me that perpetrated abuses on their ancestors. No. It wasn’t me. But I am representative of a very long history of trauma that has been passed generation to generation via complex mechanisms. That trauma continues in the form of Missing and Murdered Indigenous women, disproportionate rates of both infectious and chronic disease, systemic prejudice and racism. I heard from one KFN member who was raised off reserve steeped in shame about being Indigenous, perpetuated by cruel racism inflicted by their own non-Indigenous family members. I was told by another that they don’t call social services when a child is at risk because of the fear of families being broken up (a fair concern, given that 48% of the kids in the foster system in Canada are Indigenous) - although leaving kids in dangerous situations perpetuates cycles of abuse and trauma and all their consequences; it’s an impossible situation. The goal for many Indigenous communities in Canada is self-determination; to care for their communities and their land in the way they see fit. I have struggled with the feasibility of this. In an ideal world, we would turn back time. Indigenous nations would have evolved without the forceful influence and greed of European capitalistic and patriarchal traditions. However, the reality now seems that going back to traditional practices is impossible because of myriad factors. Discussions of food insecurity in the north (the core mission of the farm) often assume that the solutions to poor quality and exorbitantly expensive produce lie in subsidizing transportation. However, before colonial interference, communities did just fine without farms and bagged salad. But in the absence of sufficient caribou or seals due to environmental degradation and human overpopulation, or the knowhow to harvest and process them, northern communities rely on poor quality food that is incompatible with good health. In many cases, the land cannot provide adequately for the needs of the people, and may in fact poison - Grassy Narrows and Attawapiskat are but two prominent examples. Communities plagued with physical and mental illness are poorly positioned to achieve self-actualization. Imposing a “we know best” approach to reconciliation is equally doomed to fail; it is striking to me the efforts that white people are making in the north to “improve” the conditions of folks living in Indigenous communities. I don’t know if this is from a sense of guilt, responsibility, or hero-complex … or a sincere desire to connect, learn and heal. I feel it’s my responsibility as a Canadian to seek to understand, to listen and learn, to not accept blame for what’s happened, but not abdicate responsibility for building a better world and working toward reconciliation. I have a responsibility to not only acknowledge the land that I am on, but to actively advocate for strategies, resources and prioritization of Indigenous health, well-being and representation. I have much to learn about our history, about compassion, about advocacy and engagement. There are so many resources available; this blog is a wonderful start: https://apihtawikosisan.com/aboriginal-issue-primers/ I am grateful to the wonderful people at the Northern Farm Training Institute for their commitment to building relationships, healing the land, and moving towards true collaborative reconciliation. I am grateful for to the folks of KFN for the warm welcome extended to me, and I look forward to developing my knowledge and actions in a way that benefits the well-being of all.

0 Comments

|

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed